Managing Return on Human Capital

When a factory is providing its maximum return on capital it is easy to see. A third shift needs to be added, the loading dock is constantly nearing capacity with product before the trucks come to take it away, and inputs are arriving just in time to be put into production.

Return on human capital, though, requires a different perspective and analysis because of how malleable that capital is. A hydroforming aluminum press that is set up to manufacture parts of a monocoque automotive chassis cannot put out a different product without significant retooling that could take days. Humans are quite different. A senior in-house legal counsel can just open a different document and suddenly be doing the work of a paralegal–yet at several times the hourly cost. If this scenario were occurring regularly across sales, marketing, development, and operations roles, everyone at the managerial level would appear to be busy, working at capacity, yet the company would be operating well below the potential return on capital.

Return on human capital, though, requires a different perspective and analysis because of how malleable that capital is. A hydroforming aluminum press that is set up to manufacture parts of a monocoque automotive chassis cannot put out a different product without significant retooling that could take days. Humans are quite different. A senior in-house legal counsel can just open a different document and suddenly be doing the work of a paralegal–yet at several times the hourly cost. If this scenario were occurring regularly across sales, marketing, development, and operations roles, everyone at the managerial level would appear to be busy, working at capacity, yet the company would be operating well below the potential return on capital.

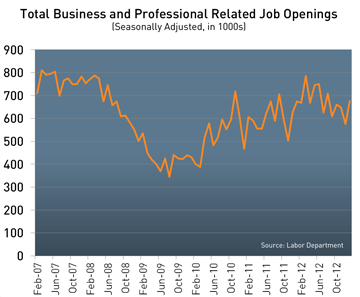

“During the recession, asking people to absorb other roles and make do with lower staffing levels helped to trim budgets and survive in lean times,” says Rob Romaine, president of MRINetwork. “Nearly three years after the end of the recession, though, employers are hiring throughout their organizations, and there are nearly 3.7 million current job openings.”

The highest job opening rate is in the professional and business sector where there is one job opening for every 27 workers currently employed, in contrast to one opening for every 33 healthcare workers or one for every 50 construction workers. Considering that the unemployment rate for management, professional and related occupation professionals is 3.8 percent, or one in 26, the sector is essentially near full employment.

“Maximizing your return on investment when it comes to professional talent today isn’t a matter of how lean you can run the organization, but rather how effectively you are utilizing your top talent,” notes Romaine. “This has been one of the largest shifts in talent demand this year. Managers aren’t just looking at the capabilities they can add to their organization, but how to add talent that will let their talent reach their highest potential,” says Romaine.

While in a simple way this might mean freeing top producers of the responsibilities that distract from them doing what they do best, Romaine says it can also involve a more nuanced approach.

“A lone wolf could do amazing things, yet appear to be peaking in their performance. By bringing in someone on a similar level but with a different background, a manager can help to spark the rigorous debate and examination that allows a once plateaued performer to continue to grow and do their best work,” says Romaine.

When talking about an organization’s top performers, though, the conversation inevitably has to return to not just how to develop them, but how to retain them. A recent survey by the American Management Association showed that more than a third of employers are expecting turnover to increase in the coming year, while less than 20 percent of those employers feel they are well prepared for that turnover.

“Top talent is driven by success, their ability to have a positive impact on their organization, and the potential to continue to grow,” says Romaine. “Building out teams that help top talent to grow is vital to increasing job satisfaction at a time when finding experienced replacements is becoming increasingly difficult. But helping your best people to work better also directly improves your return on human capital.”